The David Johnson Collection

Ancient Cypriot & other Antiquities

All the Cypriot items are being donated to the Cultural Heritage Protection Foundation which is a new UK registered Charity. Half have now been donated and will soon be repatriated to Cyprus and we hope exhibited permanently at Kykkos Monastery Museum, to be followed by the remainder.

On 23rd September 2019, 5 years after I started collecting Cypriot antiquities, an attempt was made to hand over ownership of all of the Cypriot collection to Kykkos Monastery museum in Cyprus through Tasoula Hadjitofi's NGO “Walk of Truth”. The first 87 pieces were intended to return to Cyprus in March 2020, but the disruption of freight flights by the Covid pandemic meant they were stuck in a warehouse. It was then discovered the agreement was faulty and had to be changed. I had hoped to simply make a gift to Cyprus in a spirit of trust, but hostility from the Cyprus Museum held it up further. Now that this is solved and the Cypriot government enthusiastic, I hope the first 130 objects will be able to be exported extremely soon and we hope publicly exhibited this year. Most of the remainder will follow next year or whenever a new space is ready for them. I expect a more academically rigorous printed catalogue that I am currently writing will be ready by that point.

Collecting, Cyprus and ethics

I started collecting in early 2013. I had not intended to be a collector. I had always been fascinated by time – by history and antiquity. I had enjoyed (as I still do) looking at objects in museums, visiting ancient sites, even once taking part in an excavation over a summer holiday. Then I discovered it was possible to buy more modest ancient objects quite cheaply. For me these things are not so much aesthetic objects as magical containers of the past within the moving present. Beyond simply unearthing things, archaeology is an exercise of the imagination. I bought a small piece: then a few more. At first I bought Roman and Greek objects because I knew most about them and they were basic to my own culture as a European. I could empathise with the makers in a way I found harder with ancient Egypt, for example. I also bought an Etruscan piece and a couple of pieces that were much older – just for the link to such early human history. However, if I could make just one journey in a time machine it would be to the future: the time I will never know at all.

I quickly understood that, especially as a beginner, it was important to use scrupulous, knowledgeable dealers. Many peddle fakes or are ignorant about what they sell and a few have not been too squeamish about handling possibly recently looted pieces. Having a posh shop window in the West End is no guarantee, despite inflated prices. If you live in the UK, Members of the Antiquities Dealers Association UK (less so the AIAD) guarantee that items are what they say, and will take back anything suspected not to be, even long after the sale. They tend to be the safest bet. Some also give tips about spotting fakes. Of course they take a very big cut. Or you can go to auctions of antiquities (where you are likely to pay less, despite paying an extra 40% to the auction house). However for a long time I never thought to ask where (or rather who) these objects for sale came from.

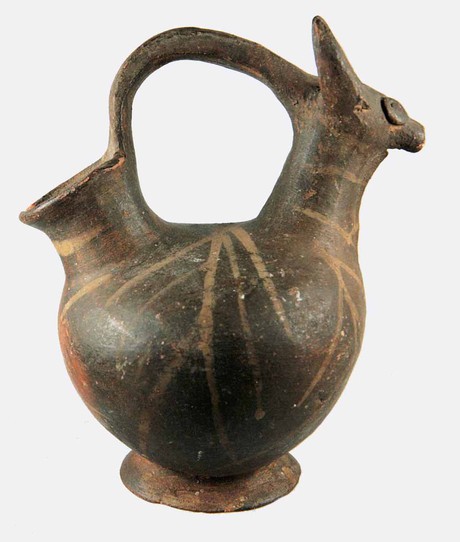

Quite soon I discovered the amazing individuality of early Cypriot pottery, especially from the Bronze Age. The wares, though derived from the Anatolian roots of settlers around 2500 BCE, were unique and highly inventive. I was impelled to explore the complexity of Cypriot history and culture. As my books didn't answer some of my questions I started to read papers, monographs and PhD theses. I wish I could take part in a Cypriot excavation but unfortunately my back would not now survive a day of bending over. Perhaps I might be accepted to do drawings?

Cyprus was at the hub of many trade routes and the chief supplier of copper (main constituent of bronze) to the Mediterranean and the near East. In the Bronze Age and earlier, Cyprus was largely independent, though for a brief period Cyprus paid tribute to the Hittites. The Late Bronze Age was a golden age and much Cypriot pottery was exported. The greatest city was at Enkomi, near modern Famagusta.

Late in the Late Bronze Age other influences mingled with the native ones, especially from Mycenae. Then the collapse of Mycenaean civilisation brought waves of immigrants who became dominant in the 10 kingdoms which formed at the beginning of the Iron Age, except in Kition (now Larnaka), which was a Phoenician colony.

In the Early Iron age Assyrians and then Egyptians laid claim to Cyprus and finally the Persians incorporated it into their empire. Native styles and those of the vanished Mycenaean Greece were mixed with Phoenician and Egyptian influences. However the mass production of pots on the potters wheel removed some of the "soul" of earlier bronze age pot shapes and the interest moves to the painted decoration. After the Geometric and then Archaic periods (1050- 480BC) the pottery and sculpture of the Classical and Roman periods became largely provincial imitations of Greek and then Roman wares, and I am much less interested.

Most well preserved objects come from tombs, not the excavation of buildings. Personally I don’t mind if objects are mended or encrusted with calcium carbonate from being under-ground. Old things should look old. However items are sometimes heavily cleaned, and missing sections almost invisibly restored. I prefer mends and restoration to be visible. You must decide what you prefer. However collectors in general prize intact, fully visible objects so those attract a premium. The large mass of plain ware pottery jugs and bowls etc from the Late Bronze Age onwards which is found in excavations is hardly seen in the sale room, possibly because the collectors don't buy them so looters didn't bother with them.

For 10 years I have only collect Cypriot objects, chiefly from the Bronze Age. Luckily fewer people collect it than Greek, Roman or Egyptian wares, and it is possible to buy significant, museum quality pieces at a more reasonable price. But, as in every field, the price for the best pieces does shoot up. However I discovered that there is a moral dilemma in antiquities collecting which is usually side-stepped but must be addressed properly.

Given the huge plundering of Cypriot tombs and archaeological sites, not only historically but in recent times (especially since the Turkish invasion in 1974) the provenance of objects has become an ethical issue. It is hard to deal with since hardly any of the less significant objects on the market has a collection history (what the market calls provenance) past the last owner and sometimes not even that. Almost none comes from a known dig site (what archaeologists call provenance). This is a general problem with all antiquities. For an archaeologist an object from the past mostly has value only if it is related to where it was found in the ground in relation to other things. An illegally dug object loses all that. It can only be identified and dated by comparison with items from proper digs, and usually adds nothing to our knowledge. The argument goes that to buy an object which might have been looted, even third or fourth hand, encourages looting. Perhaps this point is taken too far, since looters are only influenced by dealers willingness to buy and they in turn are motivated, if they are unscrupulous enough to deal with such people, by the possibility of selling in the relatively near future. Whether or not it re-sells in 30 or 40 years does not come into it. In my experience most dealers have become more careful about provenance in the last few years (thought the criminal few may have got better at faking it). A dealer I trust has told me that attitudes have changed enormously. Objects with good collection histories now command higher prices.

More recently the argument has shifted to the assertion that any purchase of antiquities supports a system which looters can feed into. Archaeologists are understandably more aware of this illegal part of the antiquities trade than the main mass of it. But even if looting could be ended, there are estimated to be around 5 million privately owned antiquities in the UK alone and most of the antiquities trade is involved with redistributing these objects as the collectors die and new ones like me arrive. There is no chance of the trade going away. These objects have to be dealt with. Someone has to look after them. A large number of the museums, even in Cyprus and especially in the USA exhibit private collections, so penalising private collections is hardly feasible.

The international standard of probity has become a known provenance going back before 1970 (the date of the UNESCO accord on antiquities), but many items without it may actually have been around before then and occasionally a bit of sleuthing can prove it. However museums, except in the country of origin, cannot exhibit items not passing this test, and are generally reluctant to comment on privately owned antiquities any more, in case it increases their value. It should be said, though, that collecting antiquities is a way to spend money not make it: collectors rarely sell and their descendants would be doing quite well to get back half of what the collector paid. It is dealers and auction houses who make the money.

Unfortunately until recently (even after 2003 when the UK signed the accord) auctioneers and dealers didn't feel any need to preserve provenance unless it was from a famous collection or collector, who's name would add kudos and thus value. They are admittedly constrained by the requirement that the identity of the seller can only be revealed with the permission of that person, but they routinely fail to get this. Also relatives inheriting these objects too often didn't understand the need to preserve paperwork (I have only come across one collection for sale where the actual date particular items were bought is known). In addition some dealers have muddied the water about provenance. Thus it is hard to distinguish recently looted items. The loot of the Victorian plunderer Luigi Palma di Cesnola formed the basis for several great Museum collections of Cypriot objects outside Cyprus, and many early archaeologists were scarcely more than treasure hunters. The contents of most private museums and collections (including in Cyprus) are, by modern definitions, looted. I now have to accept the unpalatable truth that this is also true of most of my collection.

Until recently I didn't know about the importance of 1970 so I own items with known provenance only from the 1970s or 80s. I would like to bequeath my collection to a UK museum, including those items, but Museum rules now mean I cannot. Currently such an item can be traded but not given to a museum (except perhaps in its country of origin). Wouldn't it be better for archaeology and the public if this situation were changed, at least for gifts to museums? What better solution is there for these objects? Perhaps a later rolling cut-off date could apply, in order to retain the deterrence to contemporary looters. Archaeologists and museum curators I have asked about this seem to agree (off the record). I more recently tried to buy only items with pre-1970 provenance but it was almost impossible, especially if documentary proof is required. In any case, many archaeologists seem to feel that simply by collecting I became the enemy, though collecting is the source that archaeology and museums grew out of. Confusingly, however, when I stated to an academic (at a conference on looting and destruction of antiquities recently) that I thought these objects I was collecting belonged in museums, I was told that the museum sector was shrinking and unable to deal with all these pieces and the answer was responsible collecting! But obviously the artefact has no choice in who buys it. Clearly there isn't an agreed position as I had thought. The pieces with inadequate proof of 1970 provenance remain orphans which nobody knows what to do with, but they are valuable cultural heritage and some are historically important, even without the information excavation details would have added.

Ultimately the best practical solution to looting I can see (while retaining the legitimate functions of of the antiquities market) would be some form of COMPULSORY REGISTRATION of privately owned antiquities (as in Cyprus). This would make it very hard to introduce newly looted items into the system. It might require some sort of amnesty initially (such as was, in effect, offered in 1970, to pre-1970 acquisitions), otherwise it would be hard to get people to comply. But what is more important: the ending of looting or the punishment of owners of pieces with dubious provenance? I do not envisage this as requiring the police raiding houses looking for unregistered antiquities (I am told this would be politically impossible), but rather that when an owner wished to dispose of a piece, either to sell it or donate it or pass it on, its existence on the register would need to be shown. Buyers would expect a registry number, which they could check. Even if the register was open to archaeological researchers, the identity of the owners need never be divulged, except if necessary to the police. Dealers and auctioneers would simply check the number on the register. Owners could self-register a piece on-line with downloaded photos. Photos would be essential to prevent the speculative registration by traffickers of several objects using one existing one to "reserve a place" for not yet looted items. The register would allow an overview of what exists for researchers. Whether it could be a source for requesting direct research of objects while preserving the safety of collections from thieves I don't know. If possible the amnesty would just apply to antiquities with inadequate ownership provenance. These cases are not, in any case, normally prosecuted now. Ideally it should still be possible to prosecute and reclaim objects in cases where antiquities have clear proof of having been stolen. How registration could be operated in poorer and war affected countries I don't know. Antiquities there with a valid legal status would have to be distinguishable from newly looted items, or else all export forbidden except with a hard-to get licence (as in Cyprus now). But in any case, within the rich countries which fuel the trade, the system, would function, with the spotlight turned on items newly entering it to justify themselves.

After the system was fully set up, entry from another country with a similar system would be easy. Other new items would, of course, have to be individually vetted as suspicious, which would be expensive so might require a fee. The computer system would also be expensive to set up but I hope would not require fees to register as it would be important to include no element which might discourage registration and there would need to be assurances about the security of the register, as well as assurances that items being registered did not risk being confiscated. A major dealer I have submitted this idea to told me he would be happy to sign up to it. He also thought antiquities dealers should be registered. The time taken to get through this change of the law, and the time given to people to register would need to be as short as possible, since there would be a rush by traffickers to get newly looted material through in time: the one drawback of this idea. Of course the amnesty could exclude items only known in the last few (perhaps 5?) years, which would solve this, but looters would simply claim there was provenance and it would be too time consuming and expensive to check. Also to require any proofs of provenance when registering would deter some owners and make it over-complex to do. However is there some way of suitably marking an item with its registration so that the quite possible claim to have lost the paperwork could not in future be used as an excuse?

Five years ago I committed to leave my whole collection to a Cypriot institution. It feels like a sort of justice. A small restitution of all that has been stolen. After trying other alternatives, I approached Tasoula Hadjitofi who worked hard to find several Cypriot institutions which were keen to receive and exhibit my collection. Finally on the 23rd September, 2019 an agreement was signed Through Walk of Truth with Kykkos Monastery, in the Troodos Mountains which gets about a million visitors per year. They have a museum showing a large collection of Icons and reliquaries and other religious items, as well as a small museum of Cypriot antiquities. It was hoped that my collection would gradually join it. However hold-ups due to Covid 19 pandemic has seen them stuck in a warehouse for many months. It was then discovered the agreement was faulty and it had to be rewritten, further delaying the return by more than two years. We now hope that the new agreement will be signed very as soon as the new Cultural Heritage Protection Foundation is registered in the UK as a charity and the first shipment of 123 pieces will be sent almost immediately. Most of the remainder will follow next year. This will give Kykkos time to create a new space and give me time to get used to the idea of not having my collection around me.

I collect mostly pottery and so far have concentrated on the Bronze Age. Perhaps one day I may buy more widely from the early iron age but that can wait as there is more of that period available. I am lucky that I recently inherited some money, which allows me to consider more expensive items. A few years ago I nearly bought an extremely important (and extremely expensive) piece for the Cyprus Museum, which would have been among their chief treasures, but the purchase fell through because the museum wouldn't say they supported me until the the same moment the owner decided not to sell. I wouldn't want the responsibility of looking after such an important piece, even temporarily. Space in my small house (which was already full of our books) was in any case starting to present problems for the future of the collection and my wife does not want it to feel like a museum. Though she shares my interest she feels no need to own these objects. I know I don’t really own them, though. They will go on existing in a real museums, long after I do. I am a temporary, if slightly over-obsessive guardian.

But why am I so obsessed by this imaginary Cyprus of the past which i am assembling from these fragments? As it grows it colonises my imagination. I feel I am replacing myself with these objects, as though when the rest of me disappears they will remain as a hard residue.

For an overview of the collection click on "Thumbnails". Click on any item to see more.

I hope you enjoy my catalogue. The pieces are roughly in date order.

Click on any photo to enlarge it.

Any comments, arguments or corrections are welcome. Some of my comments are now quite old and I now know more, so I should probably do a re-write at some point. Currently I am writing a more academically rigorous but compact catalogue to be printed for the museum. Traditionally this should contain descriptions. I think of this website as similar to the individual collections of images on Pinterest, except I own the objects and try to elucidate them and put them in a context.